What Challenges Might We Experience Once a Child Joins

Our Home through Adoption or Fostering?

當孩子通過領養或寄養的方式進入我們的家時,我們會遇到什麼挑戰?

By Staci England MSW, Hollie Wan B.Sc., and Erica Liu Wollin PsyD

The initial period after placement may not be as smooth as many adoptive or foster parents may hope. Issues for both parents and children can surface quickly or gradually and some parents may feel they do not have all the necessary tools to cope with the unfolding situation. Below are some questions that may arise for your family and information to help you decide how best to navigate these challenges.

“Why do I feel negative feelings or no feelings at all toward this child?”

There is a tendency on the part of parents who have chosen adoption or foster care to expect the bond between themselves and the child to develop naturally and quickly. However, it is important to be patient with both yourself and the child during the early periods of adjustment.

Not all adoptive or foster parents fall in love with a child the minute they enter the family. If this is your experience, you are not alone and it is okay to acknowledge these feelings. You have only recently met this child and it will take time to become familiar with your adopted or foster child. Similarly, these children have experienced great loss, and need time to adjust to their new home, feel safe, and learn to interact warmly with new people. You may not feel reciprocity at first, which could affect your initial feelings (Davenport, 2016).

“I’ve been eager for this child to join my home, so why am I feeling so low?”

Postnatal Depression has become a recognized struggle which is now frequently met with compassion and understanding. Unfortunately, Post-Adoption Depression is rarely discussed, although it is not a rare occurrence with 18-26% of mothers reporting some struggle. Circumstances that contribute to Post-Adoption Depression include unmet expectations, fatigue, lack of social support, discovering unknown special needs, and previous struggles with infertility (Neubert, 2012 & Nazarov, 2013).

Amy Rogers Nazarov (2013) described her Post-Adoption Depression: “Around week four, my appetite waned. I started bursting into tears for no reason at all… I became preoccupied… I began missing work deadlines, ignoring calls from friends, wearing the same ratty black pants day after day. Sleep was strangely elusive.”

Adoptive parents find it difficult to discuss these feelings because they wanted the adoption so much and have worked so hard to bring the child home. The adjustments necessary to welcome a child home through adoption require just as much time off work and support from friends and family as bringing a child into the family by birth. Yet parents may feel shame or guilt for struggling, and feel there is nowhere to talk about the way they are feeling. If you are struggling with Post-Adoption Depression, counseling or a support group with other newly adoptive parents can be helpful to address your feelings.

“I feel alone, burnt out. I have no space to care for myself.”

It is important to be mindful of your own mental and emotional condition, especially during difficult transitions. Bringing an adopted child home requires many shifts in routine, lifestyle, and identity. All of this can become overwhelming (Neubert, 2012). Well-prepared adoptive parents work hard to ensure the child’s primary attachment is established with them, and avoid lots of other people caring for or holding their children; however this can lead to exhaustion and disruption of parental self-care.

If you have not already created a community of support for your family, now is the time to enlist family and friends to be intentional in creating a nurturing and supportive environment for your family. You may need to be more willing to ask for help from your partner, your family, your community, or bring in some outside assistance. However, help that doesn’t understand the unique issues of adoption can be quite frustrating or even add stress rather than decrease it; so you may also need to help others understand your child in order to be of more help to you. A short article on talking to your family and friends can be found here (Singer, 2016).

“How can I tell if my adopted or foster child is struggling with attachment?”

Every child has a unique personality and set of experiences, so it is to be expected that some children will take a longer time to adapt to their new environment. For those who have experienced trauma, allowing themselves to feel safe and accepted by their new family can be especially difficult.

Most children learn to attach from the way their early caregivers cultivate attachment and are likely to develop the same style (Qualls, Corkum, & Buckwalter, 2019). This means attachment can be complicated for children who have been looked after by multiple caregivers due to institutional care or multiple foster placements, or for those who have experienced abuse and/or neglect.

According to Attachment Theory, children develop one of four attachment styles:

1. Secure attachment, 2. Ambivalent / Preoccupied attachment 3. Avoidant / Dismissing attachment, 4. Disorganised attachment

|

Attachment Style |

Description |

|

Secure |

● Can separate from parents to explore ● Greets parents’ return positively ● Prefers parents to strangers ● Will seek out parent when frightened or upset |

|

Ambivalent |

● May be wary of strangers ● Very distressed when parents leave ● Not easily comforted when parents return |

|

Avoidant |

● May avoid parents ● Does not seek contact of comfort from parents ● Little or no preference for parents over strangers |

|

Disorganised |

● Mixture of avoidant and resistant behaviour ● May seem dazed, confused, or apprehensive ● Around age 6, may take on a parental role toward other children or parent |

From Cherry (2020)

For children that have had strong bonds with birth or foster families, those early experiences of learning to attach will help them with attaching to you and others throughout life. But this also means they will likely need time and help grieving the loss of those close relationships.

It is a common misconception that if a child is affectionate, it means they have no attachment issues. In actuality, a child may be affectionate but solely on their terms, or overly affectionate with anyone (indiscriminate/disinhibited), or affectionate yet terrified of abandonment and thus constantly seeking affection in order to be reassured. These are all signs of potential attachment issues if the behaviour is prolonged (Qualls, Corkum, & Buckwalter, 2019).

Attachment is not an either/or concept. It is more like a continuum in which some children develop a secure attachment easily and others struggle to varying degrees. If your child is struggling to attach, it does not mean you have done anything wrong, but there may be things you can do to help. You can find out more about attachment styles through the resources below or by speaking with a therapist who is familiar with attachment issues.

“Why is my child behaving like this?”

Many parents are perplexed by behaviours they see in their adopted or foster children. If your adopted child is exhibiting difficult behaviours, here are factors to consider:

Biological Factors: Hunger, fatigue, or under-hydration can profoundly impact behaviour. Keep a regular routine with plenty of healthy snacks and water. It is a good idea to provide these before a child is overly hungry or thirsty, as some adopted or foster children have difficulty sensing their bodily cues. Additionally, vitamin deficiency or other hormonal imbalances can affect sleep, energy levels, and brain chemistry needed to manage emotions and behaviours (Purvis & Cross, 2018). You can talk with your pediatrician about supplements or medications that may help balance your child’s body chemistry.

Expression of Needs: It is important to remember that all behaviour is a form of communication. Many children in adoption or foster situations did not have responsive, attuned caregivers to show them healthy ways to express feelings. This leaves them struggling to communicate through behaviours that you may find confusing, scary, or hurtful. This table offers some possible ways to interpret behaviours that your child is exhibiting [2]

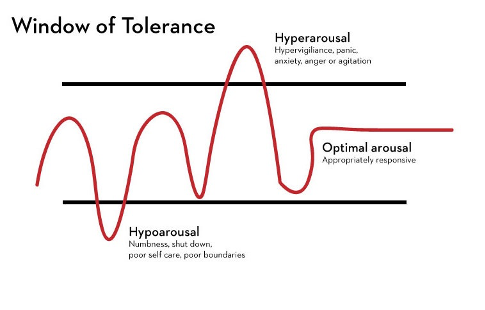

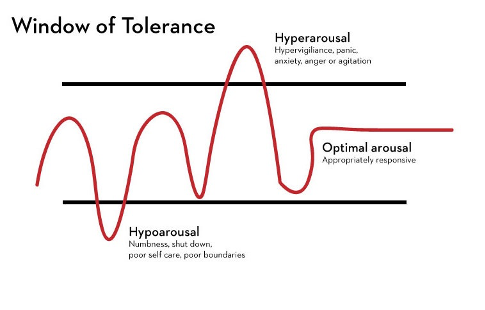

Stress Responses and Trauma: Behaviours can also be rooted in the state of your child’s nervous system. Though wired for connection, the nervous system also scans the environment for threats. Each person’s nervous system will perceive different things as threats, based on both chemical makeup and past experiences (Dana, 2018). A healthy nervous system has a wide “Window of Tolerance”, while one exposed to early adversity may have a narrower window. This can lead to stress responses that are markedly intense, or shut down (Gill, 2017, Johnson 2019).

Children can also experience trauma triggers in their environment which they cannot express. From their environments and interactions with caregivers, they also developed survival skills to help them cope. For instance, a child may learn to imitate violence or to lie to avoid abuse from a caregiver, or to steal or hoard things to make sure their needs are met. While distressing, these behaviours may have developed as a survival strategy for your child (Purvis & Cross, 2018).

Read on to learn more about trauma and how it affects our parenting.

“Has my child experienced trauma?”

It can be easy to ignore your adopted or foster child’s past experiences and focus on building a healthy new relationship. Unlike a biological child who has had mostly a shared history with their parents since conception, an adopted or foster child has also been shaped by previous experiences of which adoptive or foster parents may be unaware. This trauma can include aspects such as a birth mother using substances while pregnant or living in chronic stress, the child feeling rejected by their birth parents, being left to cry for long periods of time, and/or physical or psychological abuse or neglect while staying in birth or foster homes or institutions.

Young children also don’t remember their story in a way they can verbally express with others, but their bodies remember what they have lived through and respond accordingly (Purvis & Cross, 2018). This can be evidenced in their insecurities, behaviours, and reactions.

It is important to acknowledge what your child has or may have been through and look for patterns in their responses. We discuss trauma-informed parenting approaches next. You may also need to work with a therapist experienced in attachment and preverbal trauma specifically; a team approach to address the experiences your child has faced will make a strong foundation.

You can learn more about finding a therapist here[3] .

“Am I using parenting strategies that are not a good fit for my foster or adopted child?”

At the root of all adoption or fostering situations is an experience of loss for a child. The impact of this loss can vary based on the experiences that follow and all these experiences and memories your child brings into the home should be considered in parenting.

The experience of loss or trauma can leave children extra sensitive to feelings of rejection or prone to behaviours that they learned for survival that seem manipulative (Purvis & Cross, 2018). Parenting approaches that are mindful, offer connection, explain transitions, and share some control can reduce anxieties that lead to aggressive lashing out or silent withdrawal and shut down. In contrast, parenting that is very rigid, withdrawn, or punitive can add to the child’s fears and feelings of abandonment.

Find out more about attachment and/or trauma informed parenting approaches here[4] .

“I didn’t expect to need to parent this way. This wasn’t how I was raised. This child pushes my buttons.”

We previously discussed the attachment styles of children[5] [6] . However, every person - including yourself - has had some experience of attachment, or the lack thereof, in their childhood history. Your relationship with your own caregivers may give invaluable insight into your reactions to your child’s behaviours. Adoption therapist Karen Buckwalter gives this example: “I often have parents that … say things like ‘well, we are not allowed to be angry at my house,’ that means that person is completely unprepared for the level of anger some of these children may be expressing” (Qualls, Corkum, & Buckwalter, 2019). If your parents even now are judging your parenting, or express values and beliefs about parenting that contradict to what you have committed to through your adoption preparation and training, this may cause additional stress or confusion.

It’s important to understand why certain behaviours from your child may cause you to feel more frustrated or anxious than others. Being attentive to your own emotional status will help you thoughtfully choose responses to behaviours that may be eliciting emotional reactions and will help you notice and repair any breaks in the relationship more quickly (Bryson, 2020). These repairs in your relationship are essential for building resilience in your child.

Spend time reflecting on the nature of your relationship with your caregivers in order to gain understanding of yourself. You may also want to take the Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Scale to find out your score and understand how this might have impacted you.

Knowing your own attachment style and background may help you understand and shift your reactions, and to respond differently to your child’s behaviours, thus helping your child behave differently with you. It can also improve your own mental health! The book Parenting from the Inside Out can guide you in understanding how your childhood is impacting your parenting. You can also find out more about your attachment style here and work with a therapist so you can learn and grow alongside your adopted child.

“Is my child grieving? What can I do about it?”

Adopted and foster children often grieve the losses and transitions they are experiencing, and young children may not have the verbal ability to express what they are feeling. As adults it is important for us to pause and think about the abilities of our children, not only based on their chronological age, but also their developmental stage. Grief in children can look like sadness, rage, confusion, or relief, and it may be more likely to show itself in play or art rather than words. Grief can also be seen in regressive behaviours like thumb sucking, bedwetting, separation anxiety, aggression, or risk taking (Jackson, 2015).

You can help your child by recognizing grief in these different behaviours, and creating space to communicate about the loss with words and through art or play. You could say, “You seem really sad right now. It is hard to miss people we love. What could we do to help that hurt in your heart feel better?” Many people believe that children cannot handle the truth, but they are feeling the loss regardless. Not speaking about the loss only leaves children to grieve alone (Jackson, 2015).

You can find activities to help children process grief through The Dougy Center (National Center for Grieving Children & Families) and by working with a therapist.

“It doesn’t matter that my child is a different race than me, does it?”

It is wonderful that you as adoptive and/or foster parents love your child no matter where they are from or which race they are. If you have opted for transracial adoption, and you have noticed signs that your child is struggling, being part of a transracial family would be a crucial variable to consider as you work to understand how your child is feeling and help them cope.

Your child can experience micro aggressions - incidents of indirect or subtle discrimination - as early as kindergarten (Wintner, Almeida, & Hamilton-Mason, 2017). Being on the receiving end of micro-aggression, whether intentional or not, can contribute to struggles your adoptive or foster child is facing and should not be overlooked. Older adopted and foster children will be more aware of race and may have complex feelings or internal conflicts regarding being in a transracial family. If parents are aware of this possibility from the beginning, sensitivity to these issues can go a long way in helping your child establish trust and settle into a loving relationship.

“My child’s behaviours are very extreme. What else could be going on?”

If your child is exhibiting very extreme behaviours such as aggression which makes others feel unsafe, chronic lying or stealing, ongoing self-injury, prolonged rages, inconsolable crying, inability to calm down, or other behaviours of concern, it would be important to consider what other factors might be affecting your child. These issues could be rooted in prenatal exposure to substances which was overlooked or not disclosed, reactive attachment disorder, or another special need which has not been identified. It is also important to work with a professional who is experienced in these issues.

Prenatal Substance Exposure: A significant percentage of children in adoptive or fostering situations have been prenatally exposed to substances. There is a set of disorders caused by prenatal alcohol exposure known as Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASDs). You may also have come across this disorder being referred to as Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS), which is a type of FASD. Symptoms of FASD include inattentiveness, difficulty with behaviour and impulse control, poor memory, and difficulty with emotional regulation. For more information on FASD, you can visit FASD Hub.

Other substances such as methamphetamines, marijuana, heroin, and cocaine can also impact neurological development and lead to emotional and behavioural difficulties (Chasnoff, 2019).

If these symptoms are reflected in your child’s behaviour, and your child’s history is either unknown or would suggest the possibility of prenatal exposure, it is important to consider whether your adopted or foster child could have an FASD or a neurobehavioral disorder due to drug exposure. As with many disorders, early intervention offers the best chance for your child’s future by finding necessary accommodations and supports (Streissguth et al, 2004).

Reactive Attachment Disorder: Reactive Attachment Disorder (RAD) is a rare condition seen in children who experienced extreme abuse or neglect are unable to establish a bond with primary caregivers. Infants and young children with RAD will not smile or react to parents, appear withdrawn and disinterested in others, and will not seek out comfort from a caregiver, preferring to soothe and nurture themselves. These children may also have unexplained episodes of irritability, sadness, or fearfulness (Child Mind Institute, 2020). Some of these episodes can include behaviours that are violent and threatening to other family members, leaving parents struggling with their own fears and feeling desperate for help. For children with RAD, the previous home environment was a place of danger and the closeness family members desire is perceived as a threat, making home an exceptionally difficult place for these kids (Qualls, Corkum, & Buckwalter, 2019).

It is important to be selective in seeking treatment for RAD. There are several unproven and potentially harmful “treatments” that have been used, including restraint, deprivation, and some “boot camp” style approaches (Psychology Today, 2017). You can learn more about attachment-focused, trauma-sensitive therapy here and how to choose a therapist here[7] .

Other Previously Unidentified Special Needs: A birth parent’s mental health issues may have been a significant reason they were unable to care for their child, or an underlying factor driving substance use. This may or may not be noted in your child’s paperwork, so it is important to be aware of mental health issues or developmental conditions where genetics play a part. These include, but are not limited to: Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Major Depressive Disorder, Bipolar Disorder, Schizophrenia, Autistic Spectrum Disorder (Gandal et al, 2018), Anorexia Nervosa (Dockrill, 2019), and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (Chen, 2017).

Considering these other factors can be overwhelming, because many parents did not anticipate such challenges and were not prepared for them. There is hope, however, in the wealth of information and support groups available online. And with the support of a competent mental health professional, you can work towards an accurate diagnosis, and your family can learn new ways to adapt and cope with these challenges.

當孩子通過領養或寄養的方式進入我們的家時,我們會遇到什麼挑戰?

By Staci England MSW, Hollie Wan B.Sc., and Erica Liu Wollin PsyD

迎接孩子回家後的最初階段可能未如許多領養父母或寄養家庭所希望的那麼順利。父母和孩子之間的問題可能會迅速或逐漸浮現,有些父母可能會覺得他們沒有合適的應對方法。以下是您和家人可能會面對的挑戰和應對它們的資訊。

“為什麼我對這個孩子有負面情緒或沒有感覺?”領養父母或寄養家庭經常期望自己和孩子之間的感情會自然和迅速地增長。但是,在最初階段,對自己和孩子有耐性是很重要的。 其實並不是所有領養父母或寄養家庭會在孩子進入家庭的一刻立即愛上他。如果您也有類似經驗,您並不孤單,這些感受是可被接受的。您剛剛才遇上這個孩子,因此您需要一些時間才能認識他。同樣,這些孩子曾經經歷過重大的缺失,亦需要時間適應環境的轉變。他們需要時間去確認新環境是安全的,同時亦在學習與新認識的人交流。剛開始時您未必得到孩子熱烈的回應,這亦可能會影響您對孩子的最初感覺 (Davenport, 2016)。

“我一直渴望這個孩子加入我的家庭,為什麼我會變得如此沮喪?”

現今社會對產後抑鬱症有較多的認識,人們亦大多同情及諒解。不幸的是,有關領養後抑鬱症的資訊卻很少被討論。但是,領養後抑鬱症並不罕見,它影響著18-26%的領養母親。引致領養後抑鬱症的情況包括:尸現實和期望有落差、疲勞、缺乏社會支持、發現早前未知的特殊需要,以及與不育症相關的經歷(Neubert,2012; Nazarov,2013)。

Amy Rogers Nazarov(2013)是這樣描述患上領養後抑鬱症的情況: 「在迎接孩子回家後的第四週,我的食慾下降了。我開始無緣無故地哭泣… 我的專注力下降了… 我開始趕不上工作的進度,無視朋友的電話,日復日地穿著同樣的黑色褲子。我也失眠了。」

領養父母覺得很難去討論這些情況,因為他們非常渴望領養,並且花了很多努力才能接孩子回家。為了領養孩子而進行的生活調整與分娩孩子無異,就如父母也需要請假及親朋好友的支持。然而,領養父母可能會因為出現這些感受而感到羞愧或內疚,卻無人可傾訴。若果您正經歷領養後抑鬱症,可以考慮尋找輔導服務或參加新手領養父母的支援小組。

「我感到孤獨,精疲力盡。我沒有空間去照顧自己。」

照顧自己的心理和情緒狀況十分重要,尤其是在面對過渡期出現的挑戰。領養父母需要為著孩子的加入而適應一些新的生活習慣、方式和身份的轉變。這些轉變可能會帶來很大壓力(Neubert,2012年)。準備充足的領養父母會盡力與孩子建立穩固的依附關係,亦會避免讓孩子被太多外人照料或擁抱;但同時間,這可能會令領養父母更加疲憊及失去照顧自己的空間。

假如您尚未建立一個能支援您組成領養家庭的圈子,現在是時候邀請家人和朋友為您的家庭提供支援了。您可能需要主動向您的伴侶、家人、社區尋求協助,或尋找一些外來幫助。但是,某些提供協助的人卻可能因為未認識領養而提供適得其反的幫助,這些情況或會讓您氣憤,甚至加重您的負擔。因此,在尋找別人幫助之時,您亦能需要幫助他人了解你的孩子,這樣才能真正幫助你。這篇短文可讓您知道如何讓朋友及家人了解領養孩子(Singer, 2016)。

“我怎樣知道我的領養或寄養孩子是否在建立依附關係上感到困難?”

每個孩子都有獨特的個性和經歷,因此有些孩子將需要更長的時間適應新環境。對於有創傷經驗的孩子而言,他們會覺得比其他人更難以讓自己感到安全和被新家庭接納。

大多數孩子依照其早期照顧者照顧的方法建立依附關係,孩子其後亦會以同樣的依附方式去建立關係。(Qualls,Corkum和Buckwalter,2019)。這意味著對於曾被因多次轉換寄養家庭而被多名照料者照料、或經歷過虐待和忽視的孩子,建立依附關係可能會變得困難。

根據依附理論,孩子會建立其中一種依附類型:1. 安全型依附 2. 焦慮矛盾型依附 3. 迴避型依附 4. 混亂型依附

|

依附類型 |

描述 |

|

安全型 |

|

|

焦慮矛盾型 |

|

|

迴避型 |

|

|

混亂型 |

|

Cherry (2020)

對於與親生或寄養家庭有著深厚感情的孩子而言,他們早期學習依附的經驗會幫助他們與你或他人建立依附關係。但這也意味著他們可能會需要時間和幫助平復失去之前的親密關係的心情。

人們常會誤解,如果孩子表現得熱情,則意味著他們沒有依附問題。但實際上,孩子可能只在某些情況下表現熱情,或對任何人都過分熱情(不分生疏),這或因為對被懼怕被遺棄而展現出過分熱情的態度以得安心。若上述行為持續時間長,這些都是潛在的依附問題的徵兆(Qualls,Corkum,&Buckwalter,2019)。

依附並不是一個非此即彼的概念。有些孩子容易發展安全型的依附,而其他孩子則會有不同程度的掙扎。如果您的孩子在依附方面有困難,並不意味著您做錯了任何事情,但您可以為孩子提供幫助。您可以閱讀以下資料以更了解依附理論的資訊,或向熟悉依附問題的治療師尋求協助[WT1] 。

“為什麼我的孩子會這樣?”

許多父母對領養或寄養孩子的行為感到困惑。如果您的領養孩子表現出複雜的行為,可能與以下因素有關:

生理因素:飢餓、疲勞或脫水會嚴重影響行為。定時為孩子提供大量健康零食和水,最重要的是在孩子過度飢餓或口渴之前提供這些食物,因為一些領養或寄養的孩子很難感覺到他們身體對肚餓的提示。此外,維生素缺乏症或其他荷爾蒙失調情況會影響睡眠、能量水平和管理情緒和行為所需的大腦化學物質(Purvis&Cross,2018)。您可以與兒科醫生商討以了解是否適合使用一些有助平衡孩子體內化學物質的輔助食品或藥物。

表達需求:所有行為都是一種交流方式。許多等侯被領養或寄養的孩子的照料者對情緒並不敏感,導致孩子無法在他們身上學習表達情感的適當方式。這使他們可能做一些讓你覺得混亂、恐懼或被傷害的行為來表達他的需要。下表提供了一些方式來協助你解讀孩子的行為。

壓力反應及創傷:這些行為有可能是由孩子神經系統的狀態所致。除了與外界連接,神經系統也會探測環境中的威脅。根據化學組成的部分和以往的經歷,每個人的神經系統也會將不同的事物視為威脅(Dana,2018年)。健康的神經系統是具有寬廣的「容納之窗」,但當在年幼時遇過逆境的人,他的窗口就可能會較窄。這可能使壓力反應明顯加劇或停止運作(Gill,2017; Johnson 2019)。

孩子亦可能在身處的環境中經歷創傷,卻無法表達。孩子在他們身處的環境中透過與照料者的互動,會培養出各種生存技能 (Survival skills) 來幫助他們應對創傷。例如,兒童可能學會模仿暴力或說謊行為來逃過照料者的虐待,或以偷竊或囤積東西的行為以確保他們的需求得以被滿足。雖然這些行為令人苦惱,但卻可能是您孩子的生存策略(Purvis&Cross,2018)。

繼續閱讀以了解更多有關創傷及其對我們養育子女的影響。

“我的孩子經歷過創傷嗎?”

很多人會忽略領養或寄養孩子的過去經歷,只專注與他們建立健康的新關係。寄養家庭或領養父母並沒有意識到,孩子受著過往經歷的影響,與一直跟父母成長的親生孩子很大分別。孩子曾經歷的創傷可能包括以下情況:生母在懷孕時使用藥物或生活在壓力大的環境、孩子感到被其親生父母拒絕、長時間哭泣而沒人理會、遭受身體或心理虐待或忽視。

幼兒不能以言語表達自己的故事,但他們的身體會記住自己的經歷並作出相應的回應(Purvis&Cross, 2018)。您要確認孩子經歷過或可能經歷過什麼,並在他們的對答中尋找痕跡。接下來,我們將討論有關創傷的育兒方法。您可能需要尋找在依附和言語創傷有經驗的治療師或採取團隊合作的方式來協助處理您孩子所面對的經歷。

“我使用的教養方式適合我的寄養或領養孩子嗎?”

所有領養或寄養的情況都源於孩子的缺失。這種缺失帶來的影響會因孩子隨後的經歷而異,養父母在教養時應考慮孩子過去的經歷而做出調整。

面對缺失或創傷的孩子會對被拒絕的感覺份外敏感,或學習了一些生存而學習的操縱性的行為(Purvis&Cross,2018)。謹慎、提供心靈連繫、了解過渡期對孩子的影響、不過於操控的養育方式可以減低孩子的焦慮,亦減少孩子的抨擊、沉默退縮或閉關。相反,非常刻板、缺乏關照、懲罰性的養育方式會增加孩子的恐懼和被遺棄的感覺。

此處能讓您了解更多有關依附和/或創傷知情的育兒方式[WT2] 。

“我未曾想過需要這樣去養育孩子。。這不是我成長的方式。這個孩子讓我感到氣憤。”

我們之前討論了孩子的依附方式。但是,每個人,包括您,在童年時也有一些依附或缺乏依附的經驗。您與您的照顧者的關係可能會對您理解自己對孩子行為的反應提供見解。領養治療師Karen Buckwalter舉了一個例子:『我經常有父母……這樣說,“嗯,我們在家裡不准生氣。』這意味著這個人未完全準備好面對孩子有可能展現的憤怒情緒。(Qualls,Corkum和Buckwalter,2019)。如果您的父母現在仍在評論您的教養方式,或表達與您在準備領養時所學習到的理念有所抵觸的觀點,亦可能會讓您感到困惑或帶來額外的壓力。

您需要明白到孩子的某些行為讓您特別感到沮喪或焦慮的原因,覺察自己的情緒變化將有助您更能選擇如何回應孩子的行為,並幫助您更快地發現並修復關係中的任何破損(Bryson,2020)。修復關係對於增強孩子的適應能力很重要。

您可以花一些時間反思您與照顧者的關係以加深對自己的認迫。您可以考慮使用Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Scale量表以了解自己的童年經驗所帶來的影響。

認識自己的依附類型可以幫助您了解及改變自己的回應,並對孩子的行為作出適切的回應,從而減少孩子複製您的經驗和情緒反應。同時,這亦對您的心理健康有所裨益! 《Parenting from the Inside Out》一書可以讓您了解自己的童年如何影響您現時的教養方式。您還可以在這裡找到更多有關依附方式的資訊,並與治療師合作,與孩子一同學習和成長。

“我的孩子還沒放下過去的創傷嗎?我該怎麼辦?”

被領養和寄養的孩子通常會為自己所經歷的缺失和過渡感到悲傷,同時幼兒可能並未能以語言來表達自己的感受。作為成年人,我們必須停下來考慮孩子的能力,這不僅取決於他們的年齡,還取決於他們的發育階段。孩子經歷的悲傷看起來可能像是傷心、憤怒、困惑或釋懷,並且大機會在玩樂或藝術中展現,而非從文字,表現出來。悲傷亦可能在退縮行為中表現,例如吮吸拇指、尿床、分離焦慮、攻擊性或冒險行為(Jackson,2015)。

您可以協助您的孩子在不同的行為中分辨及認識悲傷的情緒,並創造空間用言語、藝術或玩樂就過去的缺失進行交流。您可以說:「你現在似乎非常難過,想念著自己愛的人卻不能與他們見面真的很痛苦。我們該怎麼辦才能使您內心的痛苦減輕?」許多人認為孩子們無法接受真相,但無論如何他們都感到悲傷。不談論缺失只會讓孩子們感到更悲傷孤獨(Jackson,2015)。 您可以通過The Dougy Center (National Centerfor Grieving Children & Families) 和咨詢治療師尋找幫助兒童處理悲傷的活動。

我和孩子的種族,這是沒關係的,對嗎?

您願意領養與您種族不同的孩子真的太好了。如果您選擇了跨種族領養,並留意到有跡象顯示您的孩子正在面對一些困難,那麼您在幫助他們時,如何協助孩子融入跨種族家庭及明白孩子的感受是一個重要的考慮因素。

您的孩子在就讀幼稚園時,就 可能遭受微歧視 - 間接或不顯眼的歧視(Wintner,Almeida和Hamilton-Mason,2017)。無論微歧視是有意還是無意,您的孩子正在面對的困難不應被輕視。年紀較大的孩子會更留意自己的膚色,並因而對於自己身處異族家庭產生複雜的感受或感到矛盾。如果父母及早注意到這些可能出現的狀況,並了解孩子的感受,將更有助您與孩子建立信任和親密關係。

“孩子的行為非常極端。究竟還有什麼問題?”

如果您的孩子表現非常極端的行為,例如使他人感到不安全的攻擊、長期說謊或偷竊、持續的自殘、憤怒或哭泣、無法冷靜,或其他令人關注的行為,那麼您應考慮還有哪些其他因素正在影響您的孩子。這些問題可能源於懷孕時服用而未被發現的藥物、反應性依戀障礙,或尚未被發現的其他特殊需要。與經驗豐富的專業人士合作去了解這些問題是重要的。

生母懷孕時服用藥物:大量等候被領養或寄養的兒童在出生前已接觸藥物。產前接觸酒精引起的疾病稱為胎兒酒精頻譜疾病(FASD)。您可能亦認識稱為胎兒酒精綜合症(FAS)的疾病,這也是FASD的一種。 FASD的症狀包括注意力不集中、難以控制行為和衝動、記憶力差以及難以調節情緒。您可以進入FASD的網頁[EW4] 獲取更多有關FASD的資訊。

甲基苯丙胺、大麻、海洛因和可卡因等其他藥物也會影響神經系統發育,並導致情緒和行為問題(Chasnoff,2019)。

如果孩子有這些症狀,而他的病史不明或有跡象顯示他在產前曾接觸藥物,您應考慮孩子因接觸藥物而患有FASD或神經行為障礙的可能性。與許多疾病一樣,早期對症下藥,提供合適協助,將有助孩子的未來發展(Streissguth等,2004)。

反應性依戀障礙:反應性依戀障礙(RAD)是罕見的疾病,通常發生在飽受虐待或忽視而無法與照料者建立關係的兒童之上。患有RAD的嬰幼兒不會對父母微笑或作出反應,顯得孤僻和對他人不感興趣,也不會向照顧者尋求安慰,反而會更喜歡自己去安慰自己。這些孩子可能還會出現無法解釋的憤怒、悲傷或恐懼(Child Mind Institute,2020),包括使用暴力和威脅其他家庭成員的行為,讓父母感到著恐懼和無助。對於患有RAD的孩子來說,以前的家庭環境是一個危險的地方,因此緊密的家人關係是一種威脅,這些孩子會覺得家庭是一個異常困難的地方(Qualls,Corkum和Buckwalter,2019)。

尋找RAD的治療時必須謹慎地選擇。坊間流傳著一些有害而未經證實的「治療方法」,就如約束、剝奪,或「新兵訓練營」的方法(今日心理學,2017)。您可以在此處了解更多有關以依附為本和處理創傷的療法以及如何選擇治療師的資訊[WT5] 。

其他未被辨識的特殊需要:親生父母的心理健康可能是他們無法照料孩子或濫用藥物的重要原因,但在您孩子的文件中未必有清楚寫出。因此,在留意孩子的心理健康或發育狀況時,應留意當中會否是受親生父母的基因所有影響。狀況包括但不限於:專注力不足/過度活躍症(ADHD)、重度抑鬱症、躁鬱症、精神分裂症、自閉症譜系障礙(Gandal等,2018)、神經性厭食症(Dockrill,2019)和強迫症(陳,2017)。

面對這些情況的時候,領養父母或寄養家庭可能會感到不知所措,因為他們沒有預料到這樣的挑戰,還沒有做好準備面對。但是,網上有大量資訊和支援的群組,亦有不同的兒童心理專家可提供協助。您可以朝著準確的診斷方向努力,而您的家人可以學習適應和應對這些挑戰。

資源

作為領養父母或寄養家庭,我們鼓勵您可尋找更多的資訊幫助孩子。當您認識更多,就能為孩子找到更合適的協助。網上亦有很多資源可幫助您[EW6] 。

Resources

As adoptive or foster parents, it is in your child’s best interest to find out as much information as you can in these areas. And the more you know the better equipped you will be to help your child and find the right supports for their success. There are many resources available online to help you get started.

General Information about Adoption and online communities of support:

- Adoptive Families of Hong Kong - https://www.afhk.org.hk/

- Center for Adoption Support and Education - https://adoptionsupport.org/

- Creating a Family - https://creatingafamily.org/

- The Adoption Connection - http://www.theadoptionconnection.com/

- The Honestly Adoption Company - http://www.honestlyadoption.com/

Resources for FASD and/or substance exposure:

- FASD Forever - http://fasdforever.com/

- FASD Hub Australia - https://www.fasdhub.org.au/

- NTI Upstream - https://www.ntiupstream.com/

Resources for grief:

- The Dougy Center (National Center for Grieving Children & Families) - https://www.tdcschooltoolkit.org/kids

Resources from adult adoptees:

- The Adopted Life Blog - https://www.theadoptedlife.com/

- Adoptees On - http://www.adopteeson.com/

Resources for mental health issues and challenges:

- The Child Mind Institute - https://childmind.org/

- OCD and Anxiety Support HK - https://www.ocdanxietyhk.org/

- Mind HK - https://www.mind.org.hk/

- Focus On Children’s Understanding in School (FOCUS) - https://www.focus.org.hk/

For further support tailored to your family, you can seek out an adoption and foster competent therapist. To learn more about finding a therapist for your family, read this article.[8]

References:

Bryson, T. (2020). The Power of Showing Up. I Am Mom Summit. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9Cw5JBDPbZM

Chasnoff, I. (2019, November 20). The Mystery of Risk: Drugs, alcohol, pregnancy and the vulnerable child. Insight Conference 2019. Indianapolis, Indiana. https://www.facebook.com/groups/insightlivestream2019/

Chen, A. (2017, October 17). Search Of DNA In Dogs, Mice And People Finds 4 Genes Linked To OCD. Retrieved June 13, 2020, from https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2017/10/17/558300775/search-of-genes-in-dogs-mice-and-people-finds-4-linked-to-ocd

Cherry, K. (2020, June 4). The Different Types of Attachment Styles. Retrieved August 01, 2020, from https://www.verywellmind.com/attachment-styles-2795344

Child Mind Institute. (2020, July 12). Quick Facts on Reactive Attachment Disorder. Retrieved August 01, 2020, from https://childmind.org/article/quick-facts-on-reactive-attachment-disorder/

Dana, D. (2018). “A Beginner’s Guide to Polyvagal Theory”. Retrieved from: http://www.debdanalcsw.com/resources/BG%20for%20ROR%20II.pdf

Davenport, D. (2016, August 28). "I Feel Like a Beast, but I Don't Love My Adopted Child". Retrieved from https://creatingafamily.org/adoption-category/feel-beast-love-adopted-child/

Dockrill, P. (2019, July 16). New Genetic Links Reveal Anorexia Could Be Much More Than a Psychiatric Condition. Retrieved June 13, 2020, from https://www.sciencealert.com/new-genetic-links-reveal-anorexia-could-be-much-more-than-a-psychiatric-condition

Gandal, M., Haney, J., Parikshak, N., Leppa, V., Ramaswami, G., Hartl, C., . . . PsychENCODE Consortium. (2018, February 09). Shared molecular neuropathology across major psychiatric disorders parallels polygenic overlap. Retrieved June 13, 2020, from https://science.sciencemag.org/content/359/6376/693

Gill, L. (2017, November 25). Understanding and Working with the Window of Tolerance. Retrieved June 07, 2020, from: http://www.attachment-and-trauma-centre-for-healing.com/blogs/understanding -and-working-with-the-window-of-tolerance

Jackson, K. (2015). How Children Grieve — Persistent myths may stand in the way of appropriate care and support for children. Social Work Today, 15(2), 20. Retrieved from https://www.socialworktoday.com/archive/030415p20.shtml

Johnson, C. (2019, August 16). Window-of-tolerance. Retrieved August 22, 2020 from: https://q4-consulting.com/getting-good-at-stress/window-of-tolerance/

Nazarov, A. (2013, April 03). We Adopted a Beautiful Baby. Then I Got Depressed. Retrieved August 01, 2020, from https://slate.com/human-interest/2013/04/post-adoption-depression-its-as-crippling-as-postpartum-and-much-less-recognized.html

Neubert, A. P. (2012, March 22). Expectations, exhaustion can lead mothers to post-adoption stress. Retrieved August 01, 2020, from https://www.purdue.edu/newsroom/research/2012/120322FoliResearch.html

Purvis, K. & Cross, D. (2018). TBRI 101: A Self-Guided Course in Trust-Based Relational Intervention. Fort Worth, Texas.

Qualls, L., Corkum, M., & Buckwalter, K. (2019, August 20). The Truth About RAD with Karen Buckwalter. Retrieved from http://www.theadoptionconnection.com/episode-51/

Psychology Today. (2017, June 21). Reactive Attachment Disorder. Retrieved August 02, 2020, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/conditions/reactive-attachment-disorder

Singer, E. (2016) Holidays with extended family: An opportunity for connection. [PDF]. Center for Adoption Support and Education. Retrieved July 05, 2020 from: https://adoptionsupport.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Holidays-with-Extended-Family-An-Opportunity-for-Connection.pdf

Streissguth, A.P., Bookstein, F.L., Barr, H.M., Sampson, P.D., O’Malley, K., and Young, J. K. (2004). Risk factors for adverse life outcomes in fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effects. Journal of Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, 25(4) , 228-238

Wintner, S., Almeida, J., & Hamilton-Mason, J. (2017). Perceptions of microaggression in K-8 school settings: An exploratory study. Children and Youth Services Review, 79, 594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.07.020

.png)